Nā te reta aroha ki te roopū hāpa o Aotearoa

A letter of love to the members of the New Zealand Harp Society

’Tini whetū ki te rangi. Ko Rangitāne ki te whenua’.

‘Like the multitude of stars in the sky, so too is Rangitāne on the Earth’

My name is Maria Te Rangimaria Oxnam. I am a proud woman of Rangitāne, Ati-hau-nui-a-Paparangi and Te Arawa descent. Some of the Iwi of Aotearoa from whom I am descended and much like the Rangitāne whakataukī[1] ‘Tini whetū ki te rangi, Ko Rangitāne ki te whenua’ we are like the multitude of stars in the sky, we exist upon the earth.

I am a harpist of Māori[2] descent. The distinction is necessary because while the stars maybe expansive in the heavens, there are few that I can look upon within the harping community and say No hea koe? (where are you from?), find family connection through shared whakapapa[3] in mihimihi[4] and so feel a sense of belonging and not feel alone. At best there are approximately half a dozen members within the society. Perhaps there are others yet to make themselves known. I hope this is the case, if so, nau mai, whakatau mai. This letter is also intended to give some insight to our tauiwi[5] brethren about the value of the Māori world and how this has underpinned my journey in playing the harp. I will tell you about that shortly.

Belonging

For iwi, whakataukī[6] remind us that we belong, we are not lost and that ultimately, we endure in the here and now, in the generations before us and the generations to come. Wisdom handed down to give strength to the many mokopuna[7] in times of peace and war. Whakataukī resonate and have meaning for different whānau[8], hapū[9]and iwi[10]particularly with the impact of colonisation upon our communities that continues to be felt today.

I strive for belonging in two worlds. Māori and Tauiwi. The harp, while not seen as an instrument associated with Te Ao Māori (The Māori world) the instrument has potential to lend itself to a Māori context. In fact, I would go so far as to say, all instruments can lend themselves to a Māori context. Maori have long been celebrated for innovation, seeing the value of new technologies and applying them within our world to create a fusion of dynamic sound and word.

In a recent exchange with Brian Flintoff, Master carver based in Nelson, Brian related a story about Dr Hirini Melbourne who, like Brian, was important in the revival of Taonga Pūoro, the musical instruments of Māori. Hirini once mused that the original single string instrument, the Ku, was the original guitar, but with extra strings. Apparently, Matua Hirini was inclined to be cheeky as a way of engendering ease and warmth amongst whānau and people he worked with. I wish I had met him, I think we could have gotten along well.

I came to the harp because I auditioned for a Jazz course at Hagley Community College in 2003-2004. I was one of four vocalists. I was approached by Wytze Hoesktra one of the course tutors who was also a member of a community choir we both belonged to A Capellago World Music Choir. A choir that continues today (and in whom I mihi[11] to for the wonderful world music we learned, the sense of belonging I felt in the collective sound we made, and how we shared the music from around the world with the people of Otautahi[12].

Bele

We had to audition for a place on the programme. Ensembles were built around the vocalist (This was my understanding of enrolment at the time). I imagine all other musicians who were successful would also say the same thing of their role in the ensemble. I was lucky, I was placed in an ensemble where there was an amazing Fischer Single Action Pedal Harp played by the beautiful Bele Malik. I was in awe of her then. I still am today. I am proud to call Bele my friend. There was something that Bele said that resonates now and underpins what I have done in my search to understand and play the harp. Bele said that ‘all people should have access to the harp’. A simple and elegant truth that I have lived by since.

After the course ended, Bele was leading a group of people to build a para-Celtic harp based on a design by Australian Luthier and instrumentalist, Andy Rigby. I was part of the second cohort and the reason I joined was to hang out with my friend. I valued nurturing our friendship and the building of the harp was the background to that end. It took a year to make the harp not because it was difficult in its execution, but rather, finding workshop space for seven women who had minimal woodworking skills at best (I apologise in advance if, in the retelling of this, there was amongst us, skilled woodworkers).

I remember we had access to a workshop, Bele instructed us all not to copy each other in the design holes of the sound box. I recall carving out these spaces (mine were leaves) banging a mallet against a chisel feeling like a 4-year-old at the tool bench at Playcentre. I do note with some amusement that we were in a Steiner school woodwork room and the benches were low.

We transferred to Hagley Community College woodwork room overseen by an experienced tutor. This was necessary. The machinery in that workshop space was heavy duty. We joined other groups (who were building coffee tables, cabinets etc) and I think our group stood out for the strange looking pieces of kit we would take in. As time went on, our harps began to take form. I was humbled by the tenacity we displayed in getting the project done. The group comprised women of different ethnicities and backgrounds. One mother had four children under five. I thought of these women as superheroes. They committed to the project at hand while managing the demands of their homelife. (At the time, I was part of the double income no kids’ category where the stress of getting our next coffee fix at our favourite café was the priority.) I did not know how they did it then. I still don’t know now (and now, I am a Mum).

The result after a year of camaraderie was some of the most beautiful harps I had seen. Colourful and some resplendent in delicate surface detail. There was a white harp and a blue coloured harp with a Celtic design. I chose a natural finish using linseed oil. I have wondered recently how those harps have fared over the years. I imagine they have stories to tell of the children who grew up playing them filling their homes with glorious sound. Once the harp was completed, I thought I should learn to play it.

On the 29 January 2014, I had my first lesson with Annemieke Harmonie. Prior to this, I mostly taught myself. Annemieke was a friend of Bele’s and Bele introduced us when she came to visit earlier in January. I was nervous and armed with my para-Celtic harp, I was accompanied by a close family friend Megan Jenkins (one of James’ best mates from university days) who had come to visit us. With Megan beside me, I ventured into a first lesson. I recall saying something along the lines of, ‘maybe I could have a lesson once a week for the next month and see how it goes’ I remained with Annemieke for the next 4 years or so, also starting Hannah and Ella with her when they were 5 years old.

I appreciated Annemieke’s warmth and ability to motivate me to do more. She was able to identify times where I failed to take account of my own self-care, which often might look like ‘doing too much’. This was indicated by quietly waiting in the lounge of her home and falling asleep prior to my lesson or failing to attend to a burn on my finger from cooking dinner and Annemieke fetching a plaster and salve so that I could continue to play. Annemieke also guided me in venturing out into the community to play or give comfort if the reception to my playing was less than expected. I am proud to have been a student of Annemieke’s.

Whānau, then and now

I was primed to be a student of a harp long before I met Bele. I recall waiata[13] sung by older siblings with guitar as an accompaniment. This often occurred around the formica table at home in our pink kitchen. Later I learned the paint was an undercoat. I am not sure if we lacked the topcoat because we could not afford it or whether the kitchen had been painted and therefore, we were done. Mum put up pictures from all the mokopuna[14] which to me was an exhibition of joyful colour that quite frankly made the space ‘pop’. I am laughing as I write this as my kitchen now is plastered with children’s pictures, posters (taken from performances as fond mementos) notes written by whānau[15] from birthday and Christmas gifts, letters written by Aunty Gerry and Aunty Marcia with ornate stickers, I put them on the wall to remind me that ‘we belong’ and that we are not alone and they quietly speak their affection and love into the space we call our home.

I was primed to be a student of a harp long before I met Bele. I recall waiata[13] sung by older siblings with guitar as an accompaniment. This often occurred around the formica table at home in our pink kitchen. Later I learned the paint was an undercoat. I am not sure if we lacked the topcoat because we could not afford it or whether the kitchen had been painted and therefore, we were done. Mum put up pictures from all the mokopuna[14] which to me was an exhibition of joyful colour that quite frankly made the space ‘pop’. I am laughing as I write this as my kitchen now is plastered with children’s pictures, posters (taken from performances as fond mementos) notes written by whānau[15] from birthday and Christmas gifts, letters written by Aunty Gerry and Aunty Marcia with ornate stickers, I put them on the wall to remind me that ‘we belong’ and that we are not alone and they quietly speak their affection and love into the space we call our home.

Learning through loss – Tangihanga

I remember the whaikorero[16] and moteatea[17] sung in the wharenui[18] on our urban Marae[19] in the Manawatu during tangihanga[20]. We grieved the loss of family members gone too soon. I had grown up with a silent and unspoken message that ‘in our family, we die young’. I had two sisters who died at the ages of 44 and 49. My Dad at 54 and mother at 64. If you live with an expectation of not thriving into old age, it changes your perception of time. Learning and contributing to your community therefore is a privilege and precious resource that with the passing of young family members, is a loss of potential. I am now 47 and hope I beat the odds so far dealt to us within my whānau. I remain optimistic in the face of crushing empirical data that tell me otherwise. Covid19 highlights these statistics and reminded the nation that Māori are especially vulnerable. To be clear, we have never seen ourselves as victims. We have survived the process of colonial impact, which follows a path of acquisition and enculturation. If you feel the weight of my sense of loss in these words, it is because they always weigh heavy. The whakataukī ‘like the multitude of stars, so too is Rangitāne on the earth’ takes on poignant meaning and reminds me that ‘we endure’.

On the Marae, when I heard Te Reo Māori[21] spoken and listened to the rhythmic and lilting sounds in a process of ritual encounter, this soothed and stilled me whilst sitting alongside the warm bodies of aunties, uncles and cousins seated on mattresses with blankets wrapped around us to ward off the cold air that would inevitably follow when the doors of the wharenui[22] would open (or remain open) and manuhiri[23] would be welcomed in.

In the whaikōrero[24], I would listen intently to the masterful oration of whakapapa[25] delivered by uncles who were the personification of Rangatira[26] within the wharenui. In their kōrero, they became the masters of time calling forth the names of ancestors as if to live again in those moments of spoken word. There was an eloquence where no English translation could do justice, that even the writing of this diminishes the mana[27] and power inherent in those words delivered long ago. I remember them and their delivery with great love and respect for the voices of our loved ones who now exist beyond the vale. It comforted me then and told me I was home.

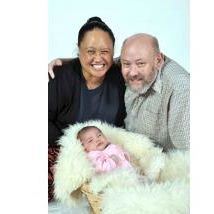

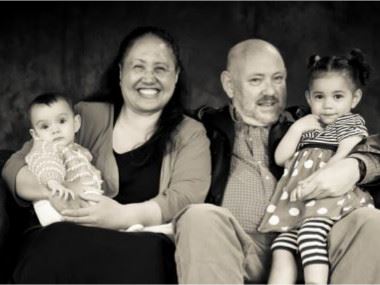

James Oxnam (11 Nov 1966 – 29 July 2013)

I met a gorgeous man while a student at the University of Canterbury. James wore a Hawaiian shirt, bandana that covered a bald head, roman sandals that covered feet with a gammy toe that never grew the way it was supposed to. His feet supported legs that Tane Mahuta [28] or Maui-Tikitiki-a- Taranga[29] would have been proud to call their own. While I have described two atua of Māori legend, James was Pākehā[30], born and raised in Nelson. He was the youngest child of Hannah and Errol Oxnam. James had eyes that changed colour with the weather, eye lashes that were like delicate tendrils waving at you, which my cousin, Nerissa noted years ago with envy and admiration. James also had the most beautiful hands on a man I had ever seen and yet to see again. His voice was warm and commanding when he needed to be (I think James would say that he had the unfortunate provincial twang that calls to mind ‘Lyn of Tawa’), an acerbic wit that was appreciated by a discerning few who knew and loved him.

It was James that helped anchor me at University in a setting that felt crushing for the sense of privilege and confidence I did not possess. I completed my degree with his love and support and in fact his proof reading (and he was tough because James was dyslexic and understood the challenges of not fitting into the academic landscape with ease). He inspired a drive and sense of ambition that I had not felt before. James’ belief in me was unwavering.

I am proud to have been loved by James. His sudden passing in July 2013 at age 46 years old when Hannah was 2 years, 4 months and Ella 8 months old was a time in our lives that should have been the beginning of enjoying our family together. I did not want to parent alone. The harp in the years that followed became a refuge and focus. I played for hours into the night after I put the girls to bed because it soothed me and filled our home with sound where once he was. I played into my grief and found solace. It was also a way of signalling that I was okay to the girls as I worked my way through a musical repertoire that challenged and delighted me.

The pain of losing him has been part of my journey and to not pay tribute to James in this space would be wrong and render my story incomplete.

Ka mamae tāku manawa tonu,

I tōku moemoea,

Homai to kupu[31]

Kia korero

Ka kite tāu kanohi ātaahua

Moe mai rā tōku Hoa Tāne Rangatira

Te Ao Māori

Waiata[32], karakia[33] and the recitation of whakapapa through whaikōrero expressed in the ritual encounter of Pōwhiri[34], the practice of these traditions laid the foundation of my musical education. I come from music that began long ago. In 1849, Matiaha Tiramorehu[35] described Māori musical tradition through the genealogy of creation.

‘Kei a te Pō te timatanga o te waiatatanga mai a te Atua.

Ko te Ao, Ko te Ao mārama, ko te Ao tūroa’

This was translated by Hirini Melbourne as,

‘It was in the night, that the Gods sang the world into existence.

From the world of light, into the world of music.’[36]

My encounter with harp therefore is a continuation of those traditions that began in Te Ao Māori, listening, recitation, repetition, rhythm and ritual have all combined.

Te Ataarangi

I have returned to the Māori language learning community Te Ataarangi[37], ki te Tauihu-a-te-Waka-a-Māui[38] as a kaiawhina[39] supporting professional development classes with the aim of teaching Te Reo in this space. Prior to this, I had been an ākonga[40] for several years, attending night classes at Nelson, Marlborough Institute of Technology. Whaea [41] Chrissy Piper, who was one of my first Kaiako[42] explained that we need to think of our learning in terms of generations. Will our children be able to speak Te Reo, or their children? ‘it takes only one generation to lose a language, and at least three generations to restore that language’. I strive to belong within the Ataarangi community so that Hannah and Ella experience Te Ao Māori in ways that I did as a child.

Hannah and Ella have continued their learning journey with harp supported by whānau across Aotearoa and led by Natalia Mann. I chose to work with Natalia as a way of supporting a Samoan sister of the Pacific. Natalia’s classical training, skilful command of improvisation, fusion of sounds the led to the group Sunga and her recent investigation of harp and environmental resonance all model a way of knowing what is possible for a daughter of Polynesia in a predominantly western setting.

Hannah and Ella have continued their learning journey with harp supported by whānau across Aotearoa and led by Natalia Mann. I chose to work with Natalia as a way of supporting a Samoan sister of the Pacific. Natalia’s classical training, skilful command of improvisation, fusion of sounds the led to the group Sunga and her recent investigation of harp and environmental resonance all model a way of knowing what is possible for a daughter of Polynesia in a predominantly western setting.

It is a cherished wish that I can take our harp onto Marae here in Te TauIhu-o-Te-Waka-a-Māui and share my love of this instrument within a total immersion environment. It seems natural, if I were to create a story about the place of a harp within Te Ao Māori, I would say, the wood that forms the body of the instrument once stood in the great forest of Tāne-Mahuta. How could a child of Tāne be denied? like me, they are being called home.

Nāku noa, nā

Maria Te Rangimaria Oxnam

Bibliography

Flintoff, Brian Taonga Pūoro, Singing Treasures, The musical instruments of the Māori, Craig Potton Publishing, Nelson, New Zealand, 2004

Maori dictionary www.maoridictionary.co.nz

Te Ataarangi www.teataarangi.org

Acknowledgement

A special thanks to the following people

Andrew and Sylvia Nevin (Nelson)

Annemieke Harmonie (Richmond, Nelson)

Aroha Gilling (Nelson)

Bele Malik (Christchurch)

Brian Flintoff (Nelson)

Dominique, Adrienne, Will and Lydia Alford (Nelson)

Emily Tuffley, Michael Moffat and Zara Tuffley-Moffatt (Munich, Germany)

Geraldine and Danny Dalleston (New Plymouth)

John Mitchell (Nelson)

Katie O’Donnell (Nelson)

Marcia Taiwhati (Wellington)

Megan, Andy, Ollie and Tessa Jenkins (Auckland)

Nadia, Gerry, Kingston and Sonny Dysart (Nelson)

Natalia Mann (Cairns, Australia)

Nerissa Warbrick (Palmerston North)

Paul Kozlovskis (Christchurch)

Villena Wilson (Palmerston North)

The New Zealand Harp Society Committee

And finally, ….to our children, Hannah and Ella Oxnam

[1] Proverb, wisdom

[2] indigenous New Zealander, indigenous person of Aotearoa/New Zealand - a new use of the word resulting from Pākehā contact in order to distinguish between people of Māori descent and the colonisers.

[3] Genealogy

[4] Speech of greeting, tribute - introductory speeches at the beginning of a gathering after the more formal pōhiri

[5] foreigner, European, non-Māori

[6] Proverb, wisdom

[7] Grandchildren

[8] Family

[9] Subtribe

[10] Tribe

[11] Thanks

[12] Christchurch, New Zealand

[13] Songs

[14] Grandchildren

[15] Family

[16] Formal speech

[17] Lament, traditional chant

[18] Meeting house, large house - main building of a marae where guests are accommodated. Traditionally the wharenui belonged to a hapū or whānau but some modern meeting houses, especially in large urban areas, have been built for non-tribal groups, including schools and tertiary institutions. Many are decorated with carvings, rafter paintings and tukutuku panels

[19] the open area in front of the wharenui, where formal greetings and discussions take place. Often also used to include the complex of buildings around the marae.

[20] Weeping, crying, funeral, rites for the dead, obsequies - one of the most important institutions in Māori society, with strong cultural imperatives and protocols. Most tangihanga are held on marae. The body is brought onto the marae by the whānau of the deceased and lies in state in an open coffin for about three days in a wharemate. During that time groups of visitors come onto the marae to farewell the deceased with speech making and song. Greenery is the traditional symbol of death, so the women and chief mourners often wear pare kawakawa on their heads. On the night before the burial visitors and locals gather to have a pō mihimihi to celebrate the person's life with informal speeches and song. In modern times, on the final day the coffin is closed and a church service is held before the body is taken to the cemetery for burial. A takahi whare ritual is held at the decease's home and a hākari concludes the tangihanga

[21] The Māori language

[22] Meeting house

[23] Visitors, guests

[24] Oratory, oration, formal speech-making, address, speech - formal speeches usually made by men during a pohiri and other gatherings. Formal eloquent language using imagery, metaphor, whakataukī, pepeha, kupu whakaari, relevant whakapapa and references to tribal history is admired. The basic format for whaikōrero is: tauparapara (a type of karakia); mihi ki te whare tupuna (acknowledgement of the ancestral house); mihi ki a Papatūānuku (acknowledgement of Mother Earth); mihi ki te hunga mate (acknowledgement of the dead); mihi ki te hunga ora (acknowledgement of the living); te take o te hui (purpose of the meeting). Near the end of the speech a traditional waiata is usually sung.

[25] Genealogy, genealogical table, lineage, descent - reciting whakapapa was, and is, an important skill and reflected the importance of genealogies in Māori society in terms of leadership, land and fishing rights, kinship and status. It is central to all Māori institutions.

[26] High ranking, chiefly, noble, esteemed

[27] Prestige, authority

[28] God of the forest and birds and one of the children of Ranginui-a-tea and Papatuanuku.

[29] Ancestor with continuing influence, godlike, although not to be confused with Christian meaning of god,

[30] New Zealander of European descent

[31] ‘Homai to kupu, kia korero’ are lyrics from the waiata aroha ‘Homai to Poho’ by Moehau Reedy and Henrietta Maxwell.

[32] Song

[33] Prayer

[34] Welcome ceremony on a Marae

[35] Ngāi Tahu; leader and teacher who led his people in the adoption of Pākehā agriculture and pastoralism and an unrelenting pursuit of land claims.

[36] Brian Flintoff, Taonga Pūoro, Singing Treasures, The musical instruments of the Māori, Page, 12

[37] http://teataarangi.org.nz/?q=about-te-ataarangi

[38] (Location) Northern (top of the) South Island and the name for the group of tribes living there

[39] helper, assistant, contributor, counsel, advocate

[40] student, pupil, learner, protégé

[41] Normally whaea denotes ‘mother’ but can also be used as a respectful address of a woman not a relation to you.

[42] Teacher, instructor